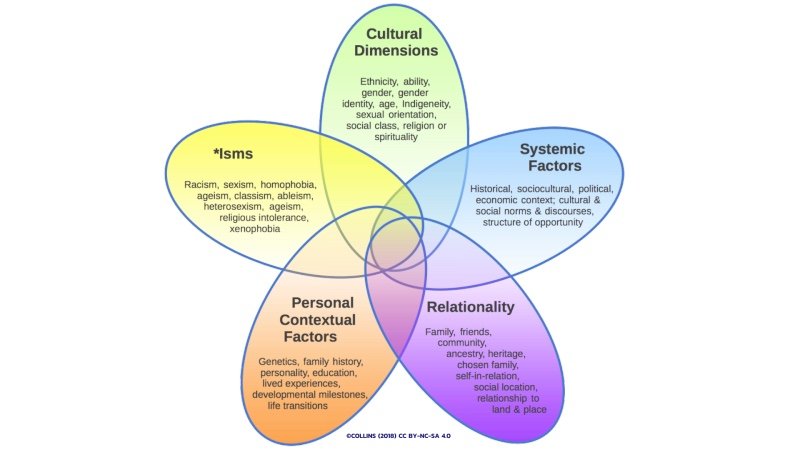

A Venn Diagram of Intersectionality: where identit(ies), equity, and inclusion intersect

©COLLINS (2018) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

A candid conversation with an Equity Sequence® learner

by Suhlle Ahn

I recently zoomed with Equity Sequence® learner Daniel Garibay, who runs a B2B sales team at a leading media company, where he has been eager to promote greater awareness about diversity and inclusion and help diversify the composition of his team. It’s why he sought out Tidal Equality on his own, and why, after completing the training, he hopes there may be future opportunity for his co-workers to do the same.

Daniel Garibay and Suhlle Ahn

Daniel works in the commercial division of his company and takes an active role in shaping the culture of the wider department. He meets regularly with four other managers toward that end.

Prior to last summer, he worried that raising D&I issues might seem too political. But following the killing of George Floyd and the awareness his death sparked, his workplace, like so many others, realized just how necessary these conversations are.

My own conversation with Daniel got me thinking about CONTEXT as it relates to questions of inclusion, marginalization, and belonging — specifically, whether you’re an insider or outsider. One marker of identity, for instance, may make you an insider in one context; an outsider in another. And markers of identity are not always visible.

Because the Equity Sequence™ is so inherently flexible in when you can apply it and how, it seems to me it teaches you to recognize inequities in context. To see how circumstance or situation may determine whether an inequity is at play.

In short, it lends itself toward an ever-evolving understanding of what inclusion or exclusion can look like.

Learn to spot the barriers, missing perspectives, and unmet needs that are stymying your work’s impact.

Intersecting Identities

Daniel, for example, is half Mexican and half British; of European Hispanic descent on his father’s side. He grew up in Mexico, where he gained a cultural sensitivity from growing up bi-cultural; raised by politically-conscious parents in a country where there is both vast wealth and vast poverty.

To my eye, as we started our zoom session, Daniel “presented” as a white male, likely of millennial age, with what sounded like a slight British accent.

And indeed, he explained that being light-skinned, middle-class, and of European heritage in Mexico actually put him in a position of privilege in that context.

“It was almost like positive discrimination,” he said.

It was only later on, spending time in England, that he began to hear derogatory comments about Mexicans, some of which came in the form of overhearing remarks from “inside” the circle, by people unaware of his complex identity.

Daniel is also gay, which added another dimension to his understanding of being marginalized. But this is not always an identity perceived at a glance in the way race and gender often are.

So two important dimensions of his identity put him outside the mainstream in ways that weren’t necessarily obvious. Yet both helped contribute to his awareness of inequality from an early age. And the ambiguous insider/outsider status gave him the ability to see inequities from many different perspectives.

“We’re all on different spectrums,” was how he put it.

Feel confident your work will have its greatest possible impact for your diverse stakeholders.

Another way I like to think of is: on a venn diagram of belonging, each of us occupies multiple circles at once, which may or may not overlap. Or, on a venn diagram of intersectionality—to use a widely-recognized term—each of us exists at the intersection of one or more social categories of identity, culture, etc. And once again, it’s context that adds meaning to the picture and forces us to adjust our perspective and interpretation.

What is Intersectionality?

The term “intersectionality” has, unfortunately, become another buzzword, and, consequently, a lightning rod for some intense reactionary backlash.

As Jane Coston explained it in a 2019 article, “The intersectionality wars”:

“On the right, intersectionality is seen as “the new caste system” placing nonwhite, non-heterosexual people on top…To many conservatives, intersectionality means “because you’re a minority, you get special standards, special treatment in the eyes of some.”

But asked for a definition during a 2020 interview, Columbia Law Professor and original author of the term, Kimberlé Crenshaw, put it this way:

“These days, I start with what it’s not, because there has been distortion. It’s not identity politics on steroids. It is not a mechanism to turn white men into the new pariahs. It’s basically a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other. We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts.”

Origin of the Term “Intersectionality”

In 1989, in an analysis of U.S. discrimination law, Crenshaw observed a problem in how courts were deciding discrimination cases when the plaintiffs were Black women.

They would determine that discrimination was or was not present, based EITHER on race OR on sex (each of these having previously been defined as a protected class), but not both.

Not, in other words, based on the intersection of the two categories.

As Crenshaw’s analysis showed, this “single-issue” or “single axis” logical framework led to varying situations in which Black women either fell through the judicial cracks altogether, or they were not seen as sufficiently representative of either category.

In one case (DeGraffenreid v. General Motors), the court ruled the Black women plaintiffs could not claim sexual discrimination, because they could not prove the discrimination they had experienced had been experienced by ALL women at GM.

In another case (Payne v Travenol), the court would not allow the Black women plaintiffs to represent their entire racial class (i.e., redress was not extended to Black men), because “the sex disparities between Black men and Black women created such conflicting interests that Black women could not possibly represent Black men adequately.”

“Intersectionality” as a conceptual framework, provided “a prism to bring to light dynamics within discrimination law that weren’t being appreciated by the courts.”

From about 2015 on—most notably, at the time of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington—the word went mainstream and began to take on a life of its own. It has since suffered a fate similar to that of many buzzwords: its meaning has morphed—its use misapplied, and its strength watered down—in what Crenshaw describes as, “like a very bad game of telephone.”

For a more in-depth review, read the Vox article, or Crenshaw’s original paper.

What is an example of intersectionality?

In her 1989 paper, Crenshaw tells the story of Sojourner Truth and her speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?,” before a Women's Rights Conference in 1851, to illustrate how an intersectional lens or prism can reveal forms of experience—and often patterns of discrimination—that would otherwise escape consideration or go unseen if you only look at categories like race and gender as distinct and separate, without looking at the interplay between, or compounding of, the two, in a person “identified” or “identifying” as both.

In 1851, (white) male critics against women’s suffrage used the argument that women were “too frail and delicate to take on the responsibilities of political activity.” Responding to this, Truth pointed to the harsh conditions and myriad brutalities she had endured as a slave—plowing fields, working “as much as any man,” being whipped, and bearing thirteen children, all sold into slavery. “And ain’t I a woman?,” she asked.

Yet, as Crenshaw points out, and as we have discussed elsewhere, early suffragettes in America did NOT, in fact, welcome Black women among their ranks, and even what historians today call “second wave” feminism is often also referred to as white feminism, because it mostly left out the experiences and needs of women of color. It lacked, in other words, an intersectional lens.

“Black women,” Crenshaw explains, “sometimes experience discrimination in ways similar to white women's experiences; sometimes they share very similar experiences with Black men. Yet often they experience double discrimination—the combined effects of practices which discriminate on the basis of race, and on the basis of sex. And sometimes, they experience discrimination as Black women—not the sum of race and sex discrimination, but as Black women."

In short, an intersectional lens allows us to explore ways in which various systems of inequality, based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, disability, and many more, interact to create unique lived experiences for people of those communities.

As a concrete example, when we look at the Roe v. Wade reversal, an intersectional lens allows us to understand how and why Black and brown women will be disproportionately harmed by the ruling.

In Crenshaw’s use of the framework—and certainly in the way we think of it—it is NOT meant to create a hierarchy of oppressions, nor to “build a new racial hierarchy with Black women at the top and white men at the bottom.”

Economic privilege within the intersectionality conversation

At Daniel’s workplace, from what I could glean, there are significant markers of privilege on display at Daniel’s workplace, revealing disparities between those coming from a certain kind of elite background, and those not.

It’s against the perpetuation of this cycle that Daniel has been trying to make a difference.

Having had some contact with elite institutions myself (and the pedigreed lot that can hail from their halls), I had a sense of what this disparity might look like.

Yet the circles of privilege don’t always match what you would expect.

Daniel believes the preconceptions can lead businesses to look at D&I in a somewhat one-dimensional way.

“If you hire a person who looks a certain way,” he offered, “but that person actually grew up in circumstances of privilege in a foreign country, are you helping combat inequality?”

To me, this gets at the heart of some very nuanced issues.

On the one hand, if we’re talking about a role that has never been held by a person of color, and you hire a privileged person of color from abroad, surely you are still breaking down racial barriers? Surely, in this case, representation matters?

At the same time, there may be other barriers, like class and economic means, that you are failing to address, but which contribute to the perpetuation of an underclass that remains excluded — perhaps one largely made up of people of color — within your country.

If the goal is to dismantle systems of privilege; possibly even challenge the notion of hierarchy itself, you may have to push beyond a given marker to see if you’re getting at the root problem or problems. You might think you’re solving an inequity when in fact you are only doing surface work.

Implementing the Equity Sequence™

This is where Daniel finds the most value in the Equity Sequence™ — that is, the integration of it as a practice into his everyday decisions.

Far from thinking about D&I as a siloed business objective — something you take into consideration only during the hiring process, or when you’re planning D&I — he likes the fact that you can invoke the Sequence™ at any given decision-making moment.

“I’m not necessarily conscious of it every day,” he acknowledged. “But it’s there in your brain. And it comes back to you in key moments.”

It came back to him, for instance, when they were doing a D&I hackathon. They were talking about leadership, and how to change their leadership. And immediately all the Sequence™ questions started coming back to him.

“We think of them as separate topics,” he said. “As in, here are these business goals. And here are our D&I goals. Like separate buckets. But they’re not separate things. If you’re not thinking about D&I as part of what’s driving your core business goals, then you’re not going to get meaningful change. Every business decision should be about it.”

“That’s the beauty of the Sequence™,” he added. “It makes you ask, what are the opportunities in whatever we do to foster more equity, inclusion, and diversity? That, to me, has been the biggest takeaway.”

I asked Daniel to tell me about some of the inequities he sees within his current work context.

Two that he brought up were the disparity between the editorial and commercial departments, and the power dynamics between revenue-producing and non-revenue-producing teams.

Changemaker Blues

In his time heading the B2B team, Daniel has tried to reshape what he felt was a quite hierarchical structure into something less so — one that is more collaborative; based more on functional teams.

And yet, he acknowledged, not entirely so.

“There’s something so innately hierarchical about the way we’re structured,” he admitted. “As the leader of a revenue-producing team, I feel my voice is heard.”

I asked what he’s done to try to change this.

“Well,” he said, “it made me re-think all of our meetings.”

And here, again, the Equity Sequence™ came into play.

“Who does this benefit? is such a helpful question,” he said. “Who’s in the room? And even of people who are in the room, who’s quiet?”

He started to question times and spaces in which he’s been more comfortable than everyone else. He’s tried to think about his relationships to those with less of a voice, questioning whether they get as much airtime. He decided to start having one-on-ones.

So he has already begun to use the Equity Sequence™ to implement tangible changes.

Then, of course, there are the imperatives of the job, which pose constraints.

“As much as I want to be non-hierarchical, you have revenue targets, objectives, and business priorities which force you to be selective with your time. If my direct reports include more senior-level people who are my main revenue producers and more junior-level people who are not, how do I allocate my time?”

Lastly, there are all the intractable, systems questions; things not within his power to solve, but which he thinks about.

“So much of what we do is around the edges,” he acknowledged, “while the fundamental issues of our capitalist system aren’t being addressed.”

“Maybe, for instance, you do something about the gender pay gap within a particular echelon of employees. But then you have all these relatively privileged people earning more equal salaries, while they’re all still making way more than everyone else at a lower level.”

Similarly, we talked about the fact that implementing gender pay equity doesn’t resolve the huge inequity between CEO pay and lower-level workers at a time of distorted CEO salaries — a problem that likely can only be addressed from outside the system.

“But at least let me do what I can from the place I’m in,” is what Daniel has concluded for now. “I can do something about recruiting, and raising awareness.”

Where do you go from here?

Now that he has done the Equity Sequence™ training individually, Daniel says he would love to experience it with his colleagues. While he’s tried to give them a sense of what it’s about, it was hard to do in a meaningful way because there wasn’t enough time, and it’s something each person has to do individually.

“But what happens if we all go on this journey together?”

He says he would love to see other people having gone through the training and then see what the collective effect of it is.

“We need people who are clued in,” he said. “In every decision that they’re making.”